Post category: easy-care garden

A bank can be a problem weedy area, but there are ways to reduce the effort. When a new house is built on a sloping site, earth-moving often leaves one or more banks, or cuttings. These can be close to the house running along one or more sides, or alongside a driveway entrance. The bank can rise back from the house, or slope away from it.

Planting a bank

In either case, a bank can present a difficult problem. The usual approach is to plant these banks with shrubs or flowers of various kinds. The result is nearly always an unsatisfactory garden feature that does not fit in very well with the rest of the garden but requires considerable maintenance effort to control weeds.

Solutions

There are three possible solutions that will reduce the effort of maintaining a difficult bank. The most obvious answer is simply to reduce the grade of the bank further. In the case of a slope away from the house, this can involve filling the slope. Then it can be grassed over as an extension of the adjoining lawn area.

If the slope is too steep to be reduced, or a boundary is in the way, an alternative is to build a retaining wall and fill in behind. Then a terrace of lawn, paving or shrubs can be installed, as appropriate.

Planting a bank

If it is not possible to soften the slope or to terrace it, the third option is to plant it with suitable plants. Trees, shrubs and perennial flowers should be planted up just as a full-scale mixed border would be, not just relying on ground-cover plants and low-growing plants alone.

If the bank is near a boundary, the bank/border should run back to the boundary with trees filling the back. The advantage of mixed planting is that it is easier to maintain than a motley scatter of low shrubs or groundcover alone, and it looks much better. The slope is lost among taller plants whereas low plants just mirror the slope.

Compared with a conventional lawn, a wildflower meadow, or a wildflower lawn, has considerable advantages, the most important being the reduction in mowing. Mowing requirements can be cut to a fraction of that required for a good lawn.

Wildflower meadows

Another significant advantage is the removal of the necessity to apply fertilizers or weedkillers. A wildflower area makes a change from manicured lawns; it is a beautiful feature in itself, and very appropriate for a certain kind of garden.

Maintenance

A lawn can be maintained as a wildflower lawn, encouraging the wildflowers, or ‘weeds’, instead of killing them. A lawn grown for wildflowers needs mowing less frequently, about every two to three weeks instead of every week, giving the flowers a chance to open. Mulch mowing returns the nutrients to the soil. Fertilizers might be used but only once a year at most and at a low rate of 10 to 15 grams per square metre, not using high-nitrogen lawn fertilizer, which encourages grass, but general fertilizer which encourages the flowers as well, or an autumn lawn fertilizer. A wildflower lawn, note this is not a meadow, is a very practical labour-saving approach for smaller gardens.

There is a big reduction in effort when a lawn area is turned over to wildflower meadow, especially in a large garden. Instead of mowing once a week from April to September, no mowing at all is done before the end of June, or early July, just like a traditional hay-meadow. After cutting, the grass is left for a few days to shed seed and then removed to a compost area. Subsequently, the re-growth of grass is mown every four or five weeks to keep it tidy.

The cut grass must be removed to reduce the fertility of the soil. This, in turn, reduces the vigour of grass growth and encourages wildflowers – the exact opposite of looking after a quality lawn. For the same reasons, no fertiliser is given, or lawn weedkiller applied, to a wildflower area.

The process of creating a successful wildflower area takes a few years. The reduction of fertility and the build-up of wildflowers takes some time. It can be speeded up by removing some of the top-soil, and by planting wildflower seedlings raised in pots. However, if the object in converting to a wildflower area is to reduce effort, these techniques are unlikely to be adopted.

Wildflower meadows

The single big cut in July can involve considerable effort. For a small wildflower area, the grass can be cut with a strimmer and raked off. For larger areas, a rough grass mower, or mowing machine will be required, and these can be hired. However, the job of mowing gets easier as the meadow settles down, and infertility increases.

Even in the early years, it is still a lot easier than weekly mowing. This feature suits large gardens best because it can look a bit messy in a small garden. A close-mown boundary where wildflower meadow meets paths and driveways helps to tame an otherwise unkempt look.

Maintenance

Generally, a large pool requires less attention than a small one. A larger body of water is more stable than a small volume which tends to get polluted and overgrown more quickly. If a pool can be fed naturally by a small trickle of water, it makes maintenance much easier.

Garden pools

A large pool takes up space that might otherwise be sown down to grass, usually. Only requiring the clearing out of surplus plant growth every year, a pool is easy to maintain. It takes a great deal of effort to put in place but relatively little subsequently. Because they are generally deeper, large pools contain relatively more water and a natural balance is more easily achieved and maintained.

A small pool tends to warm up more quickly, goes green with algae more readily and becomes contaminated with leaves and debris more easily. Plants fill the space of a small pool more quickly and need reduction more frequently. If fish are kept, they need feeding regularly. In terms of ornamental value, a small pool is far more effort than a large one, and probably best avoided if the aim is to reduce effort.

Gravel beds are widely used to reduce the proportion of the garden covered by lawn, the idea being to reduce the work of mowing. Gravel areas need practically no maintenance compared with lawns, flower beds or borders, and they compare well with solid paving.

They have the advantage over paving of being cheaper and easier to install. Gravel sets off many plants very nicely. However, the location of gravel areas, and whether or not they contain plants, can affect their value for reduced effort.

Gravel beds

Gravel beds are easy to maintain if they contain few or no plants. If the gravel is sufficiently deep 8 to 10 centimetres – very few weeds will come through. These can usually be pulled by hand. The weedkiller Simazine can also be used, except around non-woody plants.

All gravel areas need to be raked over occasionally to leave the surface even, but this is relatively light work. Gravel beds close to trees tend to suffer badly from falling leaves and germinating tree seedlings, typically sycamore and ash. Unless removed, leaves rot down to provide excellent rooting material for weeds. Although Simazine can be used where there are no non-woody plants, it will not control tree seedlings.

As time passes, gravel beds tend to sink into the soil and must be topped up. A lining of polythene, or woven polypropylene, beneath the gravel can reduce sinking but tends to encourage the accumulation of debris among the gravel, and consequently more weed growth.

Though relatively expensive, paving has the major advantage of requiring very little maintenance. By increasing the area of garden under paving, a resultant reduction in labour requirement can be achieved. Relative to any other garden feature, paving of any kind needs practically no work.

Paving

All kinds of paving need to be swept of debris and dust occasionally to prevent a build-up that would allow moss and weeds to grow, but this is a very light task compared with maintaining a similar area of lawn, for example.

Where there are cracks, or joints in the case of concrete slabs, weeds are likely to get established. These can be difficult to remove physically but there are many excellent products for their control, such as Hytrol, Pathclear or other path weedkiller, and Casoron G granules.

Climbing plants can be labour-intensive but some kinds are easy. Climbing plants and other wall plants can be used to decorate walls and fences and turn empty wall space to good advantage. Some climbing plants can creep up walls and fences by means of suckers and aerial roots but most, such as the clematis shown, need some support to cling onto, or to be tied onto. Choosing the ones that creep by their own means, such as ivy and virginia creeper, avoids the need for tying-in.

Hedges

Regular tying-in of wall plants can be very time-consuming, and the easiest way to approach the task is to wire the whole wall first, or at least that part of it where plants are to grow. It is by no means necessary, or even desirable, to cover an entire wall with climbing plants, but the aim should be to wire the area which the climber will fill.

Wires can be placed in horizontal lines about 30 centimetres apart, from about 60 centimetres off the ground right to the top of the wall. Galvanised steel wire is best, attached to brass screws at about 40 centimetre centres along each length. If a wall needs painting, these screws can be removed and the plants taken down.

Hedges are labour-intensive and may not even be necessary. Is there a wall behind the hedge? Or can a wall be made higher or a fence set up as a replacement? But if it is necessary to have a hedge, there are strategies to reduce the effort involved. A hedge provides privacy and shelter, and a good backdrop for flowers and shrubs, but it is labour-intensive, the amount of work being directly related to its size.

Hedges are sometimes planted unnecessarily beside a garden wall to hide the bare concrete. Disguise can be achieved more successfully, at less expense and with less maintenance, by using climbers, shrubs and standard trees.

The other major aspect of the size of a hedge is height; the higher the hedge, the more clipping and the more difficult to reach. A hedge of 1.5 metres has twenty per cent less clipping than one of 1.8 metres.

Tall hedges might be needed in a garden that is overlooked but, for privacy on a level site, a hedge does not need to be more than 1.65 metres high. Any hedge higher than this cannot be clipped from the ground. Higher hedges need higher ladders, or some kind of scaffolding. This adds greatly to the work because it is more difficult to clip a hedge from a ladder, and the ladder will need to be moved.

A wide hedge takes up more garden space and makes more work in reaching across to clip the top. All hedges grow most vigorously at the top and the wider the hedge the more top-clipping necessary. All hedges should be trained to a wedge-shape, in cross-section, to keep the top narrow and allow light down to the sides.

Types

The species of hedge has a big influence on the amount of clipping work. Some kinds like privet, lonicera, Cotoneaster lacteus, Leyland cypress and Monterey cypress are very rapid growers, capable of making a decent hedge in four or five years, but they also need most maintenance. Lonicera and privet need to be clipped at least twice and as often as four times each year to stay neat.

Slower-growing hedges like beech, yew, griselinia, thuya, lawson cypress, hawthorn, hornheam, berberis, olearia and holly hold their neat look with a single clipping each year. Feeding has an influence on the growth rate of hedging.

These slower-growing kinds can be speeded up in the initial years of establishment by feeding and watering. If this is done, they lose nothing in speed of establishment to the faster-growing kinds, but have the distinct advantage of easier maintenance for life.

Clipping

Clipping should be done before the young shoots begin to get woody. This process begins in July and by mid-August the job of clipping will be much more difficult. At the same time, clipping too early will encourage new growth and necessitate a second clip later.

Powered hedge-trimmers make the work much easier, but they also need care in handling to get a neat finish. Petrol-engined trimmers cope more easily with long runs of hedge, large hedges and tougher material. The cables of electric trimmers can be awkward over long runs of hedge, but they are cheaper.

Laying out polythene or similar sheeting before clipping makes tidying up much easier. Alternatively, if the clippings fall onto a lawn area, and they are not too plentiful, a rotary mower with a grass-bag can be used to chew them up and collect them.

Every container needs effort but there are ways to reduce the effort. The greater the number of containers planted up, the more watering will be necessary during the summer. It is best to restrict the number of containers to the minimum necessary and concentrate on looking after those properly.

Container plants

In any garden, there are a few key locations for containers. These are usually associated with entrances, paths, paved areas and corners of buildings. Pick out the important locations, by moving containers around if necessary, and plant up that number only.

Size

Large containers hold a greater volume of compost, and a larger reserve of water and plant nutrients. Deep containers dry out more slowly because they have less compost surface area relative to their volume.

Clay and concrete containers look good but they dry out quickly. They can be lined with polythene sheeting to keep the moisture in. Metal urns look well, especially lead and cast iron, and they dry out more slowly. Plastic holds in the moisture but does not look great.

Compost

Compost containing half peat, half good garden soil, unsterilized, with some fertiliser added is a suitable mixture. It costs less than using peat-based compost alone. If it dries out, it is easier to wet than peat-based compost, and there is a small reserve of nutrients in the soil if feeding is neglected. It also reduces vine weevil damage. Do not use garden soil on its own; it tends to become compacted with regular watering and the plant roots are starved of air.

Watering

Various ways to reduce the frequency of watering have already been mentioned, but another important tactic is to accustom the plants, from the beginning, to getting by on less water. If container plants are watered each day, they will grow luxuriantly but wilt very quickly if watering is missed for any reason.

Container plants

If they are watered every four or five days, they will become less leafy, probably carry more flowers, and they will certainly be able to stand up to water shortage much better. A low-cost automatic watering system can be fitted to reduce the effort of watering pots and other containers and are ideal for handing baskets. Use slow-release fertilizer granules.

A fully-stocked greenhouse takes a lot of time and effort but there are easier ways. Many gardens have greenhouses, empty or grossly under-utilised, standing testimony to the amount of effort a greenhouse requires. A greenhouse can be put to many uses and makes it possible to grow a wide range of plants, but only if the garden owner is interested in plants.

Greenhouse growing

Plants in a greenhouse are completely dependent on the gardener, which is fine if the gardener wants the work of caring for them. There is watering, feeding and ventilation to be considered, as well as potting up, pest control and some weeding.

However, it is possible to use a greenhouse effectively with relatively little effort. The most minimal use for a greenhouse is to plant it with long-lived plants like ivy-leaved geraniums, agaves, clivias, epiphyllums, abutilons, jasmine, hibiscus, even camellias and hydrangeas if there is enough space.

Watering

Watering is by far the biggest part of the work of a greenhouse. During the summer, tomatoes, for example, need watering every second day, perhaps even every day during very hot weather. This can be most interesting fun, or a real nuisance, depending on your point of view.

There are a number of ways to make greenhouse watering easier. To avoid carrying water, have the water supply close to hand, ideally piped into the greenhouse itself. A lazy, but effective, way to water a greenhouse quickly is to take a hose and spray over the whole lot. Plants that do not need much water tend to get over-watered with this method. There are various automatic watering systems available involving drip watering and wet-mat watering.

A rockery is often put in to save effort; quite the opposite is the usual result. As a garden feature, rockeries are frequently badly sited and badly made. Very often, any problem slope or awkward corner seems to invite a rockery as the solution – usually the worst possible choice. Far from being easy, it is very difficult to succeed with a rockery.

Rockery

A rockery must be sited, ideally, on a gentle slope in full sunshine. Very few rock plants like shade. Try to position a rock garden so that it fits into the slope and rises naturally out of it. It should not back onto a boundary wall, or a fence. There is quite a bit of work in building a rockery, especially if it is done properly.

Weeds

Small rockery plants are not adapted for competition with weeds. Weeding is usually a major job, made more difficult by the niches between rocks that make weeds hard to dislodge. Weedkillers cannot be used.

Before planting a rockery, make sure that the soil is completely weed-free. It is worth waiting a few months and controlling weeds properly. When the plants are in place, or beforehand if preferred, cover the soil with at least 5 centimetres of gravel or broken stone. Make sure that the colour of the gravel matches the stone of the rockery.

The layer of gravel will reduce weeding dramatically, as long as weeds are never allowed a foothold. Besides, the gravel helps to make a rockery seem more natural, and it sets off rock plants very well.

If traditional flower are avoided, less work is the result. Traditional formal flower beds, containing bedding roses or bedding plants, require quite considerable maintenance in terms of edging, weed control and plant care. Formal flower beds have large areas of bare soil that invite colonisation by weeds.

Flower beds

Many gardens have too many flower beds, or the flower beds are too distant from the house to be worthwhile. Quite frequently, flower beds are unnecessarily placed beside paths and driveways, offering little decorative value.

Almost without exception, formal flower beds should only be considered at the base of the house walls or internal garden walls, flanking paved areas, or decorating grass terraces. A flower bed near the house can be smaller, but more effective, than a flower bed some distance away.

It is often possible to remove inappropriate, or surplus, flower beds; reducing the number of flower beds offers considerable savings of time and effort.

Formal rosebeds

Bedding roses are the most common kind of garden roses, generally grown in a formal rosebed of rectangular, semi-circular, or some other geometric shape. These have all the drawbacks, in terms of effort, mentioned above. Yet, because bedding roses are formal plants, a formal rosebed still provides the ideal setting.

Flower beds

By keeping the number and size of rosebeds small, it is possible to greatly reduce the amount of edging, pruning, weeding and spraying. Bark mulch is sometimes used on rosebeds but tends to be messy and is not really suitable.

Informal roses

For those who like roses but not the attendant bother of going them in a formal bed, it is possible to grow them at the front of a mixed border. In this situation, they can be planted a bit less formally – more randomly spaced in a group of five or nine bushes, for example. The edging job will be largely dispensed with.

Flower beds

The ground at their base could be planted with alchemilla, sedum roseum, small campanulas, even catmint or centranthus for the taller rose varieties. When the ground cover is established, there will be little difficulty with weeding.

Crocuses or tulips could be placed in clumps to brighten the scene in spring while the rose leaves are still expanding. This kind of planting extends the season of interest for an area of ground informally planted with roses, but would be inappropriate and messy in a formal rosebed.

Formal flower beds

Formal beds of half-hardy annual flowers are very popular, but labour intensive. The flowers must be replaced twice each year to give a separate spring and summer display. This means digging the flower bed twice a year, apart from edging and weed control.

In the case of flower beds, there is no possibility of chemical weed control The only available method is hoeing and considerable handweeding. In addition, watering will usually be necessary to get the young plants established.

Keep the area planted with bedding plants to a minimum, and like formal rosebeds, keep them near the house itself. A common mistake is to have a big formal bed or bedding plants away at the bottom of a large lawn where, if it can be seen at all from the house, the bed looks no more than a splodge of bright colour.

If a decision is made to save effort and not grow vegetables at all, it is still worth growing some herbs for fresh-picked flavour. Most kitchen herbs are perennials that come up each year; apart from an annual tidy-up and an occasional run-over with the hoe during the summer, a small herb plot needs no work.

Herbs

Herbs that are easy to grow include, sage, thyme, mint, french tarragon, chives, and marjoram. Fennel gets big and could be included as an ornamental plant in a mixed border. Horseradish can be grown in some rough corner. Rosemary is a pretty shrub for the border too.

Parsley is a little awkward to grow because it must be sown each year; try it in April and July. Basil is a very nice herb but must be grown indoors in a greenhouse, or on a windowsill. Three or four plants are very little trouble and will give plenty of leaves for freezing.

Vegetable growing takes time, but some kinds are much easier than others. Many people no longer bother with vegetables at all, feeling that they are too much effort. Growing bulky vegetables in an ordinary garden is more or less a waste of time. Potatoes, cabbage, cauliflower, carrots and onions can be bought more cheaply than they can be grown in a home garden. Some first early potatoes, that will not need spraying, are nice to have, and some early fingerling carrots too, and maybe some spring cabbage.

Vegetables

Vegetables that are best freshly picked from the garden are worth growing – lettuce, radish, salad onions. These are easy to grow, and the easiest vegetable of all is french beans. Also very easy are white turnips, swiss chard, mangetout peas and leeks. All of these crops can be sown where they are to grow to maturity; they do not need transplanting.

Weed control is the main issue in vegetable growing, although sowing, thinning and transplanting take up time too. The secret of weed control with vegetables is to make sure the plot is weed-free to start with. Then, never let the weeds go to seed.

Regular light hoeing is the easiest way to keep on top of weeds. It is remarkable how large an area can be kept free by hoeing for an hour about every two weeks during the growing season. Growing vegetables in a raised bed (as shown) makes it much easier to control weeds and digging is almost non-existent.

Fruit-growing can be time-consuming but there are ways to keep the effort to a minimum. Fruit trees and bushes need pruning, weed control and picking, and possibly spraying. Often the trees are simply ignored and the results are poor. However, a small number of fruit trees takes up little time and they can be grown for their ornamental value as well as for fruit.

Fruit growing

Apple, pear and plum trees all have lovely blossom and, sometimes, good autumn colour as well, especially the pear trees. Fruit trees can be grown in a mixed border of trees, shrubs and perennial flowers, or they could even be grown as specimen trees within a lawn area.

Neighbouring gardens usually contain fruit trees that act as pollinators, so there is no need, in this situation, to have more than one or two trees. Most fruit trees are now available on dwarfing rootstocks which keep them from growing too large. These smaller trees are much easier to manage. Choose varieties that are disease-free, such as ‘Discovery(shown), ‘Katja’, ‘Lord Lambourne’ and ‘Red Devil’.

Fruit trees can also be grown as trained trees on walls, making good use of space and providing wall cover. However, they will require more pruning and training then free-standing trees.

Other fruits like raspberries, blackcurrants and strawberries are a mixed lot. Raspberries are easy to grow but they must be pruned and tied up each year. Strawberries need no work once they are planted. Blackcurrants are slow to pick; the fruit is not versatile in kitchen use, and there is pruning as well. So by making a choice, fruit growing can be made easier.

Trees, shrubs and flowers planted together in a mixed border are easier to look after because they fill in the space, denying room to weeds. The overall ornamental impact of using the various plant types together is much greater than restricting the types to their own kind, as in herbaceous borders and shrub borders.

Trees, even just one or two, can be used at the back of such borders with shrubs to fill in beneath, and in front of them. Around the shrubs and in front of them in turn, the perennial flowers provide colour and lush foliage to contrast with the hard stiffness of the woody plants. Annual flowers, bulbs and even roses can be used at the front of mixed borders to add further interest.

Mixed borders

In a mixed border, it is possible to have two layers of foliage covering the soil over most of the area, which reduces the work of weeding. Shrubs and perennial flowers can be used to hide areas of bare ground beneath trees at the back of mixed planting.

Weedkillers can be used to keep down weeds around trees and shrubs where there is no under-planting of perennial flowers. Where there are perennial flowers, bark mulch is a good alternative.

Compared to a flower bed, or island bed, a border requires edging only along the front edge. In small gardens, it is usual for borders to back onto the boundary. In large gardens, they might back onto internal boundaries or areas of tree planting. Borders with gentle curves have the advantage over straight borders that the edging need not be so frequently attended to without looking unkempt.

Many kinds of perennial flowers need practically no maintenance. However, some kinds do and it is wise to choose carefully. Perennial flowers come up year after year, unlike bedding plants that must be planted each year. This is a big saving of effort; the more garden space given over to perennial flowers instead of annuals, the better.

Perennial flowers

Even though they grow out each year, these non-woody plants die down at the end of each season. Effectively therefore, they are self-pruning. Perennial flowers are very quick to get established, requiring little watering, and some kinds are very good at competing with weeds. With each passing year, the original plant spreads outwards to form a clump and claim more ground for itself. This is ground denied to weeds.

Planting

Unlike trees and shrubs which can be planted into dead sod, it is best for perennial flowers to have the soil dug over and cultivated before planting. But it is possible to plant into dead sod too. It is essential to get these plants off to a good start. Otherwise, their ability to compete with weeds will be much reduced.

For the first two or three years, it is worth dividing and re-planting the original plants, such the candelabra primulas shown. This technique, which initially requires more effort, results in a quicker filling-in of the ground area and subsequently reduces the work of weed control.

Perennial flowers

The achieveing of complete control of perennial weeds before planting perennial flowers will save endless effort later. There is no possibility of using weed killers once the perennial flowers have been planted, and control of perennial weeds will become extremely difficult and time-consuming.

At least two applications of Roundup or similar will be necessary to kill off all existing vegetation. If chemical control is ruled out, meticulous digging up of the roots of perennial weeds, though not wholly effective, is one way to remove perennial weeds in advance of planting.

Alternatively, old carpet or plastic sheeting laid over the ground for about twelve months provides a relatively easy and effective, if slow, method of control.

Weed control following establishment is made more easy by selecting perennial flowers that cover the soil surface. The less soil left bare, the fewer weeds come through. Hoeing is relatively easy if the weeds are not allowed to grow taller than 5 centimetres and certainly never allowed to go to seed.

Hand-weeding is much slower but will probably be necessary close to the plants. A mulch of bark chippings is very effective around perennial flowers, especially in the early years until the plants begin to cover the soil.

Aftercare

Perennial flowers need relatively little regular care and attention. They need far less effort than annual flowers and roses, for example. In fact, if some care is taken to avoid the ones which need dividing and staking, most kinds need no more work than shrubs.

The lifting and division of perennial flowers to keep the plants vigorous is often advised. It involves lifting, dividing and re-planting every three or four years. However, this work is not at all necessary for many species, and some positively dislike being shifted. The ons that need it are those which have a bald spot in the middle of the clump and they tend to wander. A decision can be made not to grow these plants, or to reduce them to a minimum.

Because the stems of perennial flowers are not woody, some kinds tend to be easily blown over by wind, and need to be staked. Many others, however, do not need staking – choose these. Heavy feeding with manures, while encouraging bigger displays, also contributes to the problem of floppy stems, on plants such as the Peruvian lily shown.

Perennial flowers

When perennial flowers die back in autumn, many books advise the removal of the dead flower stalks. However, these are best left in place until early spring, because most kinds are ornamental through the winter. They also provide over-wintering shelter for many beneficial animals.

When they are cut down in spring, it is a good idea to remove the stems to only half their height. The remainder is often quite stiff and will provide a measure of support for the new shoots. The top half of the dead shoots can be removed by clipping with a hedge-clippers.

Also when left until spring, the old shoots of many perennials have rotted at soil level and come away at the slightest tug, which is much easier that cutting them.

The debris can be removed to a compost heap, or simply chopped up and left to rot down around the plants. Removing only part of the stems by clipping reduces the amount of effort involved and makes it possible to tidy up a large area of perennial flowers very quickly. A strimmer can be used fro this job too.

For easy maintenance, shrubs are next best after trees. Shrubs can be used in small gardens to fill space in the same way that trees can be used in large gardens. Many of them are fast-growing and quickly fill a considerable area. A piece of ground planted with shrubs has a much lower maintenance requirement than a similar area of lawn. Therefore, the conversion of part of the garden area to accommodate shrubs reduces effort. Many shrubs clothe themselves with foliage down to ground level, which increases their competitive ability over non-woody weeds.

Weigela florida ‘Variegata’

Planting

Most shrubs are grown in containers and sold as container-grown stock with their full root system intact. This means that they are easy to get established. When planted during the late autumn or early spring, they are unlikely to need any subsequent watering, except possibly during drought spells. This is a considerable saving of effort.

Because they have their full root system, container-grown shrubs can be planted during the growing season. However, this means losing the advantage of reduced effort because they must be kept watered until well established.

Shrubs can be planted through dead sod, as described for trees, but each shrub must have a proper planting hole dug out. This should be 10 to 20 centimetres wider all round than the rootball from the pot. Loosen the soil over a wide area, then take out the planting hole in the centre and plant up.

Pruning

Shrubs vary greatly in their requirement for pruning; some kinds rarely if ever need pruning, some need occasional thinning to keep them neat. However, no shrub need necessarily be pruned as a matter of course. Where there is space, they can be let grow as they please.

However, space is a limiting factor in most gardens and the main reason for pruning shrubs is to keep them within bounds. If you prune out roughly the amount of growth the plant puts on each year, then it will stay about the same size, or only slowly get bigger.

No pruning is necessary at all for the first five or six years, or until the shrub is flowering well, if it is a flowering kind. Then, remove about one in five of the plant’s branches each year, choosing the oldest ones to go. Most shrubs flower best on young growth so this will not upset flowering.

Do not remove part of all the branches because this interferes with flowering. Never trim a shrub with a hedge-clippers unless it has fine foliage like that of broom, heather or lavender. The principle is to thin out the shoots, not shorten them all back.

Some shrubs like rhododendrons, magnolias, pieris, enkianthus, and most evergreens are best not pruned at all. Pruning applies mainly to bushy, twiggy shrubs that produce a lot of new growth each year, particularly from ground level or near it. Choose shrubs that rarely, if ever, need pruning, and give them adequate space. This approach can reduce, or remove, the necessity to prune shrubs at all.

Weed control

Although shrubs are competitive against weeds, in most cases they are not as competitive as trees. Whereas trees only need a high level of weed control for the first five or six years after planting, there will be a need to maintain proper weed control throughout the life of a shrub planting.

Weeds selected killed among young shrubs

Hoeing is a good method of weed control among young shrubs. It is not time-consuming if the ground is completely free of perennial weeds before planting, and if the seedling weeds are controlled before they reach 5 centimetres.

Mulching can provide a major saving of effort as an alternative to hoeing. Bark mulch is the best choice because it is free of weed seeds. It must be laid on weed-free soil to an even depth of 6-8 centimetres. Grass mowings are very effective too, but not deeper than 5 centimetres at a time. Garden compost is not really suitable for this purpose because it contains weed seeds.

It will be necessary to remove weeds that manage to establish themselves on the mulch, either by pulling or by directed spray of Roundup. If willow herb builds up as it is resistant to Roundup, use Weedol or Bio Weedfree.

By choosing plants that need least care, the amount of effort in garden maintenance can be greatly reduced. Trees are the easiest group of plants to look after – the bigger the area of trees that fill the garden, the less work involved. Trees intercept light before it reaches the ground, and their deep root system gives them access to supplies of soil moisture and nutrients that smaller plants cannot reach. We can use the success of trees to our own advantage.

Trees

Because trees grow large, they can be used to fill space. Trees can look after themselves. Once they get above the grassy layer, they are away. As time passes, their competitive advantage becomes so great that grass and weeds find it difficult to grow. The ground layer beneath trees becomes dominated by plants which tolerate shade.

Planting

Trees are best planted as young plants two or three years old. The smaller plants establish more successfully and produce better anchor roots for the future. But they are also easier to plant than larger sizes; they do not need staking, and they are cheaper.

In the establishment of large areas of trees, using small plants, a number of short-cuts can be used. Although it is desirable to dig, plough or rotavate the area to be planted, it is not essential. The existing grass and weeds can be controlled by two applications of Round-up or similar glyphosate-based product.

Trees

Planting should be carried out in late autumn and early spring. The dead sod can be simply cut in an L-shape with a spade, and the sod lifted. The young tree is slotted into the hole and the sod firmed back in place. Using this method, it is possible to plant several hundred trees in a single day.

Weed control must be kept up for the first few years. After that, the trees themselves will be able to keep control. Only elder, briars and large perennial weeds will need control. Feeding the young trees in the early years will result in quicker establishment and bring forward the day when weed control can be abandoned.

Thinning

In a natural situation, a surplus of young trees attempts to colonise a free piece of ground. In time, some will dominate the rest, and there will be losses. Similarly, in establishing garden woodland planting, it is desirable to slightly over-plant to start with. Planting at a random spacing averaging two metres apart will ensure a quicker cover of the soil surface, and will provide for early losses.

Trees

After eight or ten years, it will be necessary to reduce the number of trees by about half, choosing the poorer specimens to go. These can be cut down and removed. Further thinning, again by about half the number of trees, can be carried out twenty or twenty-five years after planting.

Garden woodland can be established to cover very small areas – as little as a few hundred square metres. Small trees like birch, alder, hazel and holly could be used in smaller gardens. Where there is plenty of space to fill, the large forest trees like oak, ash, beech, elm, lime, pine, horse chestnut, spruce and sweet chestnut are ideal.

Established woodland has an extremely low maintenance demand, needing only the occasional control of woody weeds and ivy. The life of such a garden feature will range from one hundred years for birch to several hundred years for oak and Spanish chestnut.

Size

Despite the seeming ease of maintaining a lawn, there is no more time-consuming garden feature. It may only take half an hour to an hour to mow the grass, and that does not seem long. However, when the accumulated hours of a whole season’s mowing are added together, it becomes obvious that no other garden feature takes as much time.

It is estimated that 1 square metre of lawn takes three minutes to mow each season. One thousand square metres takes about fifty hours in a season. The amount of time depends on the frequency of cutting, the lawn layout and the mower used.

Lawns

But there are ways to reduce the burden of lawn-mowing. The first solution to consider is to reduce the area of lawn. Every reduction in the space given to the lawn means an equivalent reduction in time spent mowing every week, and every season!

A reduction in lawn area is easily achieved by widening existing borders, or creating borders where there are none. It is quite amazing how much space can be taken out of a lawn by adding even quite a narrow border.

Although reduced in area, the impression of size will be little affected. In fact, a small lawn backed by an ornamental border can look much bigger than a larger lawn that is not well bounded. This occurs because the space is defined by the new boundary.

Obstacles

A lawn with sharp corners and awkward angles takes much longer to mow. Little strips of grass between flower beds or shrubs present further difficulty. Flower beds, shrubs and trees dotted about the lawn turn it into an obstacle course for mowing. Each one has to be circled, pushing the mower under the low-hanging branches.

Lawns

The removal of some, or all, of these obstacles by lifting and relocating shrubs or young trees, or removing a flower bed or two, makes mowing much easier.

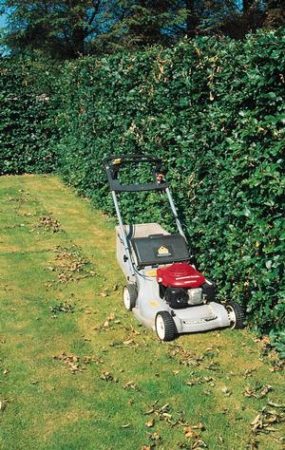

Mowing

The most important aspect of achieving a good lawn is regular, correct mowing. Although this sounds like more effort, it is in fact compatible with reduced work. Mowing frequently – at least every fortnight in the spring and every week during good growing weather – is easier because there is a smaller amount of grass to remove each time. Irregular, infrequent mowing makes the job much slower and more difficult when it is finally tackled.

Mow to a height of 2 to 5 centimetres, no tighter. Grass at this height retains enough foliage to be able to compete; mowing too tightly encourages weeds and moss. Over-close mowing tends to shave little humps, making the job more difficult and the result less satisfactory.

Lawns

The kind of mower used, and its size, make a big difference. Rotary mowers with a single blade are more robust. They are better at mowing grass when it is slightly damp. They are also faster than cylinder mowers although the latter give a more even cut and a better finish.

The bigger the mower, the less time spent mowing. A 53 cm wide mower will cut a given area in thirty per cent less time that the 40 cm mower. There are other advantages to using a large mower. The chances are that, because it takes less time to mow, the mowing will be done more regularly. The work is easier and the lawn will be of better quality as a result.

A powerful mower is less likely to break down than a small mower which is forced to struggle. Although the initial cost is higher, a large powerful mower can cost less per year of mowing, apart at all from the mowing time saved.

Lawn edges can be very time-consuming to keep neat but there are ways to reduce the effort. Usually lawns are delimited by beds, borders, walls, paths and driveways. In each case, there is a low maintenance way to fit the lawn to its boundary.

Lawns

Where beds and borders join a lawn area, the usual thing is to have an edge cut down into the soil of the border. The lawn is trimmed to where it protrudes over the edge. Usually these edges are made too deep, making it difficult to run the mower over them. It is best to have edges no more than 5 centimetres deep. The wheels on one side of the mower can be let down into the bed or border, cutting the edge easily.

A mowing strip of bricks or paving slabs can be set down in the soil of the bed or border to make a level run for the mower’s wheels. The mowing strip should be set about 2 centimetres below the level of the soil. A rotary mower has advantages when it comes to cutting lawn edges. The spinning blade creates a suction effect which lifts the grass into the path of the blade. Cylinder mowers have no lifting effect.

Mowers can only cut horizontally and even with the lifting effect of a rotary mower, the grass still grows out horizontally over the edges. Edges still have to be trimmed occasionally – less frequently if the rotary mower is used. Mowing strips facilitate the lifting/cutting action of rotary mowers and they also make it easier to trim the grass that the mower does not reach.

Where the lawn meets a wall, the narrow strip of grass next to the wall is impossible to mow because the wheels of the mower are in the way. The solution to this problem is to remove the sod and lay a mowing strip along the wall base, or to spray a very narrow strip with Roundup, twice each year.

Where the lawn meets a path or driveway, the level of the lawn should be slightly higher than the path or drive. If the path has a kerb, it will be higher than the path but just below the level of the soil of the lawn. In this way, the path or driveway acts as a mowing strip along its length.

Lawns

Where the lawn level is below that of the path or drive, the situation is the same as that beside a wall. The solution can be adopted, if it is not possible to simply bring the level of the lawn up to the herb height.

Reducing the number of lawn edges is the best way to reduce the work of edging. Beds can be filled in. Borders can butt onto paths, rather than have a strip of lawn between a border and a path making two extra lawn edges to trim. Edging can be greatly speeded up by using a power edger or strimmer. The latter is fast but not as neat.

Most plants will not grow well in shade and we invite trouble by growing sun-lovers in the wrong place. Most plants need good light but some tolerate shade. If a plant that needs sunshine is planted in the shade, it will not grow well and will need to be moved. Avoid this effort, or the loss of the plant, by placing it correctly from the outset.

All plants need light but some have adapted to coping with less than full sunshine. These are mainly woodland plants that must make do with whatever light reaches the woodland floor. They have evolved strategies to cope with reduced light.

Avoid planting in shade, unless suited

Climbers have developed the ability to climb up host trees to reach the light. Under-storey plants like holly, laurel and rhododendron have often got darker foliage with greater amounts of green chlorophyll to make best use of the light that reaches them. Very often these are evergreen, which allows them to make growth early in the year before the leaves come on the deciduous trees overhead.

Some woodland floor plants have bulbous roots that allow them to grow very quickly early in the year, flower and produce seed before mid-summer. Many of the spring bulbs fit into this category. Some woodland plants have broad thin leaves to present as much surface area as possible to the light above.

At the same time, this flimsy foliage is protected from weather damage by the trees. For example, ferns are natural shade-lovers that generally open their fronds at the same time as the trees unfurl their protective leaves.

Many plants have also adapted to growing in the full glare of the sun. Without it, they will not flower well and might even die after a while. Many of these plants are natives of open grassland or scrub areas where there are no large trees to cast shade.

Avoid planting in shade, unless suited

Very often, plants that like full sunshine also like dry soil, but not always. Equally, the ones that like shade do not always like moist soil. In fact, many woodland plants are adapted to withstand drought caused by the competition of the tree roots – another excellent reason for getting all the growing done in the early part of the year and dying back to a bulbous root during the dry summer months!

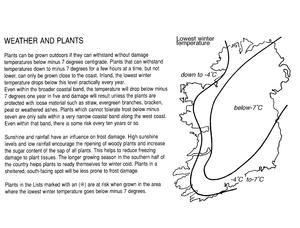

While it is interesting and challenging to grow plants beyond the range of their cold tolerance, it increases the risk of frost damage and creates more work in protecting them – taking them indoors in winter, for instance. It is important to be aware of how the local climate behaves in the garden.

Avoid plants that do not tolerate frost

The nearer the garden is to the coast, and the further south, the longer the growing season and the less likely there will be severe winter frost. There are many plants that will survive light frost down to minus 5º Celsius and will suffer below minus 7º Celsius. The chances of going below this temperature increase dramatically inland and further north.

Try to find out exactly how frosty the area is by looking at other gardens. Plants like cordyline, hebe, fuchsia and pittosporum are good indicators of the relative mildness of the area. If they have grown to good size, the winters much be fairly consistently mild. If they are completely absent, the locality is prone to severe frost.

Because of the warming effect of the sea, it is possible to grow plants in coastal gardens that would not survive inland, although wind damage near the sea is generally more severe.

The damage caused by winter cold is influenced by other factors. Warm sunny summers encourage the development of tough woody growth and high sugar content in plant cells. Freezing will not occur until lower temperature levels are reached.

Plants growing in free-draining soil will have a longer growing season and complete their preparation for winter earlier than those on heavy soil. Plants growing on south-facing slopes suffer less because the extra warmth encourages better development of tissue.

Plants struggle if they are not in the correct soil conditions. Soil conditions can greatly affect the growth of plants. Some kinds like light, dry soil; others prefer heavy moist soil. Most plants like soil that is open and well-drained but does not dry out excessively in summer. Some plants need lots of organic humus in the soil. If the humus does not occur naturally, and you are not prepared to dig it in, simply avoid those plants.

Use only plants that are suited to the soil conditions of the garden. This will avoid having to move them when they fail to thrive, or having to remove a dead plant and go to the trouble of buying and planting something else.

It is important to realise that parts of the garden might vary. Dry spots can occur near walls where the rain cannot reach. Wet spots can result from poor drainage or compaction. It is important to choose plants that like the conditions available to them.

If acid-loving plants are grown on limy soil, they will require much more preparation for planting and more care in the following years. Acid-loving plants suffer from iron deficiency on limy soils; the youngest leaves turn yellow. Some lime-loving plants such as flowering cherries lack sufficient calcium on acidic soils.

Match the plant to the available conditions

A simple test can be carried out using kits that are available in any garden shop. Alternatively, look at local gardens to see whether rhododendrons are growing in the open soil.

For an easy-care garden, it is best to avoid planting lime-haters in limy soil, and it is best to be at least aware of the effort this will require.

Gardening is not an exact science. In approaching any aspect of gardening, there are a number of possible solutions. While the different approaches can be equally correct, some are easier than others. If you choose to take an easier path, the time and effort involved in gardening can be significantly reduced. Gardening can become less physically demanding and more mentally stimulating!

Some garden features require more time and effort than others. By eliminating, or reducing, the labour-intensive garden features and replacing them with labour-saving features, time and effort can be saved – without any reduction in the beauty or interest of the garden. In fact, the quality of the garden very often can be increased. However, the garden shown would have high labour requirements.

Introduction

Plants will succeed, and need less care, if the conditions are right. Plants are living organisms that want to stay alive and will do so if they have the right conditions. As gardeners, we are the providers of conditions for garden plants, and it is up to us to see that they are provided with suitable conditions. This means finding out the needs of plants and supplying them, if possible, and to avoid growing certain plants if we cannot provide the right conditions.

First of all, take note of the garden in terms of local climate, soil, size and situation. Then before buying a plant, find out what it needs. If the garden cannot provide it, forget about growing that particular plant. There are lots of others: equally beautiful, equally interesting!

Plants are fiercely competitive about staying alive: they compete vigorously with each other for space and light above the soil, and for nutrients and water below soil level. We can use the competitiveness of plants in the battle against weeds and therefore make life easier for ourselves. The garden shown will be much easier to keep.

Introduction

Equally, plants are far from helpless against pests and diseases. They have very good defence mechanisms against both – another aspect that we can take advantage of. But remember that plants can only defend themselves if they are growing well in the right conditions – the right plant in the right place.

Easy-care gardening is smarter gardening. It requires a little more thought to avoid physical effort and expense. Easy-care gardening is gardening with Nature, not gardening against Nature. Mother Nature always wins and the challenge for easy-care gardeners is to intervene as little as possible to achieve the desired results. Work with Nature – don’t fight it!

Weeds are a problem in every garden but if the competitive abilities of plants are used to the full extent, the chore of weeding can be greatly reduced.

Because a plant cannot move position to a more suitable place, it is forced to compete where it is growing. Competition for light and space takes place over ground, and for water and nutrients, below soil level.

Every plant competes for light, water and nutrients. Some are much better at the struggle than others. Trees, for example, are the top competitors, which explains how they managed to cover the Earth with dense forests – they would again, given the chance!

Plants compete well with weeds

The trunk of the tree holds the canopy of leaves higher than competing plants. In a mature broadleaf forest, the massive array of foliage traps eighty per cent of the sunlight and about the some proportion of rain. Down below, the smaller plants must get by with the remainder.

By way of complete contrast, tiny alpine plants are adapted for survival on the cold windswept slopes of mountains where, despite plenty of other difficulties, they have no competition. Their success depends on the ability to tolerate conditions that would kill other plants.

When they are planted in gardens without the harsh conditions to which they are adapted, they are easily swamped by bigger plants, even relatively small weeds such as annual meadow grass.

If we use garden plants to cover the ground and fill the available space, the plants we do not want – weeds – will not be as difficult, or as time-consuming, to deal with: that is the principle of ground cover.

Plants compete well with weeds

In a natural setting, there is rarely any bare soil to be seen. Even land slippages, and river banks stripped of vegetation by floodwaters, are quickly reclaimed. Any piece of bare ground is colonised by plants, especially the great opportunists of the plant world – the common weeds.

To clear the soil of weeds, and leave it bare, is to offer a further invitation which will be gratefully accepted. A general principle, the less bare soil in the garden, the less work of weeding. Bare soil can be covered up with desirable plants and mulches, or in some cases, it can be treated with chemical weedkillers.

All garden plants compete vigorously for space and resources. Trees, especially the large forest trees like oak, ash, beech, elm, lime, pine, horse chestnut, spruce and sweet chestnut, are very dominant, smaller trees less so but still capable of dominating in the absence of larger trees.

Shrubs are generally fast-growing and stake a claim to their space quickly. Perennial flowers do a lot of their competing below ground level by means of extensive roots. Annual flowers grow quickly to fill their allotted space.

It is important to realise that every plant, from the largest tree to small annual flowers, has potential for ground-covering. Very often, the term is applied only to low-growing, ground-hugging shrubs and perennial flowers. These are certainly good for the task, but it must be realised that all plants have this ability, if we care to use it.

For best results against weeds, one layer of plant ground cover is better than none, but two or more layers are even more effective.

Because plants have a hierarchy of size – large forest trees, smaller trees, shrubs, climbers, perennial flowers, annual flowers in that order – they arrange themselves under natural conditions in several layers of vegetation.

Plants compete well with weeds

In natural woodland, the top layer is the forest canopy of large trees. The under-storey layer contains the smaller trees like holly, yew, and hazel together with the trees of woodland clearings like cherry, hawthorn, crabapple and birch.

Lower again are the shrubs and climbers. Then, the perennial flowers and grasses that colonise the soil below ground with their extensive root systems, or bulbous roots. The last layer of all is the moss layer, usually ignored for garden purposes but it can be important. This consists of mosses, liverworts, lichens sometimes and small ferns. These compete for resources and can interfere with the germination of seeds of weed plants.

Each layer catches some sunlight for itself and thereby makes life more difficult for the plants below. We can use this feature of the competitive nature of plants to our advantage. Instead of setting up one layer of ground-cover plants to shade out weeds, why not have two or more layers?

The various layers of vegetation can easily be set up in garden woodland planting because it approximates to a natural woodland. Large gardens of two thousand square metres, or more, can easily accommodate some woodland planting.

The various layers of vegetation can easily be set up in garden woodland planting because it approximates to a natural woodland.

In any size of garden, mixed borders of trees, shrubs and perennial flowers compare to natural woodland edge, with shade-tolerant plants meeting those that enjoy full sunshine. It is possible to use the shade-tolerant kinds to underplant trees and shrubs, and to use the sun-lovers in front of the taller woody plants.

Some plants cannot tolerate wind exposure and these will be more trouble to care for and should be avoided in windy areas. Assess the level of wind exposure in the garden. Unsuitable plants will suffer severe damage, and this may create a lot of work with shelter screens and staking. If plants, such as the phormium shown, are chosen for their ability to resist wind exposure, a lot of expense, effort and repeat planting will be avoided.

Choose suitable plants in a windy area

Strong winds affect the growth of plants in a number of ways. Wind lowers the temperature of the air around plants and reduces their rate of growth. It causes moisture loss from the leaves during dry weather and increases the damaging effects of frost during cold spells.

Apart from these effects, wind can cause direct physical damage to leaves and stems. Young leaves are very soft and easily damaged during their expansion in springtime.

Plants that are adapted to withstand the effects of wind usually have small, often narrow waxy leaves. Heathers and needle-leaved conifers are wind-resistant, for example. Many grasses and other non-woody plants have flexible stems that bend and twist away from the wind. Trees that leaf up late in the spring like ash and sycamore are relatively wind-resistant.

Near the coast, the wind problem is more severe because of greater wind speed off the sea. Added to that is the salt spray carried by strong gales, and sometimes even sand. Some plants are well adapted to salt spray in their native habitats. They can be used near the seaside as ornamental plants in their own right, and also to protect less resistant plants.